Marthe Richard vs. Mata Hari: The mythologising of a French Spy

Conference on French cinema to 1940 - Wednesday 9 April 2008

French Institute London

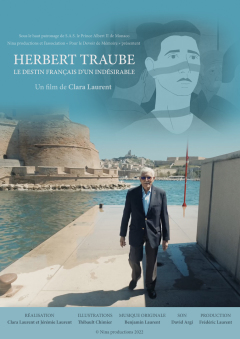

Clara Laurent – Paris X University

Pierre Lethier – King’s College London (COPYRIGHT)

On 20 April 1937, cinema screens in France were graced by a new heroine – the young Edwige Feuillère/Marthe Richard, vanquisher of Germany’s spy networks in Spain. In the space of a few rousing sequences, she coolly dismantles the dastardly operations of the grand master of U-boat warfare, and eventually guarantees the US Navy a safe passage for its convoys across the Atlantic. Raymond Bernard’s film is not only the celebration of a remarkable woman – a spy whose unique combination of versatility and virtue succeeded in uncovering the secrets of German U-boat deployment – but also the triumph of patriotic feeling and necessary revenge. Raymond Bernard was one of the many who saw trouble brewing in the world around him, and his film was a deliberate ploy to impress one thing on the French public in 1937 – the crucial importance of Intelligence in matters of national defence. Two main sources provided the raw materials which he and screenwriters Steve Passeur and Bernard Zimmer fashioned into a screenplay – the memoirs of Major Georges Ladoux, the head of French military counterespionage, and those of Marthe Richer, which in the years 1934 and 1935 had already reached a wide reading public. Women spies had become all the rage during the inter-war years, and frequently lit up cinema screens in triumphant performances by the biggest stars of the day. Two legendary, indeed scandalous figures were well on the way to achieving immortality in Hollywood movies and in German cinema – the stateless Mata Hari and the German Fraülein Doktor. For Raymond Bernard the challenge was to come up with another compelling female spy character, but this time she needed to be French.

We will analyse how Bernard achieved his aim by establishing Marthe Richard, the sympathetic French secret agent. We will thus examin the great care Raymond Bernard took in casting the right actors for the parts – in Edwige Feuillère, who was already a star of the screen by virtue of her audacious performance in Lucrèce Borgia, he had chosen an actress who was gradually fashioning herself the screen persona of a ‘strong woman’ (as Geneviève Sellier puts it). To play opposite the young actress Raymond Bernard chose Erich von Stroheim, whose reputation as a misunderstood genius and a devilishly flamboyant actor was already strongly established from his Hollywood career, but who plays with Marthe Richard his very first role in a french movie. Marthe Richard au service de la France is, then, a film centrally concerned with the fabrication, or attempted fabrication, of a new myth – the ideal Frenchwoman as spy – and a choice vehicle for two actors who had reached a pivotal point in their respective careers.

Synopsis

Lorraine, August 1914. Marthe Richard’s mother and father are shot dead by German soldiers. With no news from the front of her fiancé André, the distraught young woman heads for Paris, where she is recruited as a secret agent by Major Rémond. Her mission is to go to San Sebastián in Spain and make contact with the German spies von Falken and von Lüdow (the latter being the man who ordered the execution of her parents), convincing them that she wishes to work with them. Marthe soon has von Lüdow in her thrall, much to the displeasure of his mistress, a famous dancer who goes by the name of . . . Mata Hari. Insanely jealous, Mata Hari enlists the help of von Falken and Pedro, the owner of the club where she dances, to foil the plans of von Lüdow and her supposed rival. Von Lüdow, who is both in love with Marthe and wary of her, sets her a mission – to destroy a number of aircraft at Villacoublay airfield. Armed with a faked photograph supplied by Rémond, Marthe succeeds in convincing him that she has carried out his instructions. She also manages to scupper von Falken and Mata Hari’s plans to sabotage several French arms factories. Her final mission is to locate the German U-boat base in Spain, which she manages to do with the help of André, who has escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp and fled to San Sebastián. Marthe has her revenge, revealing to von Lüdow both her trickery and her hatred of him. The German takes a lethal injection and, his face a picture of love and reproach, dies at Marthe’s feet.

I – 1937: the gathering storm in Europe and the character of the female spy

With the beginning of German rearmament in 1935, the military reoccupation of the Rhineland and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, many people in France were growing anxious at what looked like the increasing possibility of another war in Europe. Jean Renoir, for example, documented his concern at the danger posed by Nazi Germany and the increasingly evident signs of impending war in the left-wing weekly Ce Soir during the years 1937 and 1938. As Jean-Pierre Jeancolas states, in 1937 war was on everybody’s mind: ‘The pre-war was already under way – in military headquarters, in factories and in people’s consciousness.’[1] That year saw the release of a number of films containing overtones of war; as Ginette Vincendeau has observed, at this point many filmmakers had served in World War I, and were keen to demonstrate that they were upholding France’s military traditions and concerns.[2] In his 1938 film Cavalcade d’Amour (which did not reach cinema screens until 1939), Raymond Bernard gives Michel Simon the solemn and portentous conclusive line: ‘The post-war years are over.’

Faced with the prospect of another world war, French cinema’s response was to follow Renoir’s lead by harking back to the terrible hardships and the outstanding acts of courage witnessed in World War I.[3]Thus in the years 1936 and 1937 two types of film became especially popular in France, both of them involving intelligence agents and spies:[4] In the first type of film, the secret agent operates in a contemporary setting. Examples include the Capitaine Benoît series and Double Crime sur la Ligne Maginot. In the second type, national or international spies are involved in special operations or other secret activities in World War I. It is in the second type of film that female spies tend to play a leading role in the plot.

American cinema had already popularised the character of the fatale female spy in films such as Dishonored (1931), starring Marlene Dietrich, and Mata Hari (1931), with Greta Garbo in the starring role.[5] Garbo played the infamous dancer and courtesan executed by the French in October 1917, a historical figure who from 1922 onwards became a truly global myth.

The myth of Mata Hari itself has a fascinating history: as the polemic regarding the strength of the evidence against Mata Hari gradually rose, the French judges who ordered her execution broke their silence. In 1922 Major Emile Massard, who had played a role in Mata Hari’s trial in 1917, published an authorised work, Les Espionnes à Paris (Women Spies in Paris), with the professed aim of ‘informing those serving on the front of what had been going on behind the lines’. A keen film buff, Massard begins his account justifying the 3rd War Council’s execution of numerous women convicted of spying or other acts of treason with the words: ‘This is the story of a formidable band of traitors, women skilled in the dark arts of disguise, desertion, drug abuse and double-crossing . . . in short, ideal material for a good American movie’. He goes on to give the decisive, irrefutable evidence which condemned the dancer to the firing squad – that Mata Hari, alias H21, received money from Hans von Krohn, the German naval attaché in Spain. Several American newspapers had revealed details of Mata Hari’s mixed Jewish-Protestant background, fearing an unfair trial, to which Judge Jean Chatin responded in a declaration published in his friend Massard’s book: ‘Well, my judgement is based on firm PROOF, material which I have held in my hands, as well as on the foul spy’s own testimony, in which she admitted to having caused the deaths of anything up to 50,000 of our children, in addition to those who were on board vessels in the Mediterranean torpedoed thanks, no doubt, to information supplied by H21. Furthermore, we should not forget that H21 was in Germany in July 1914, where she was the mistress of a German prince, and that after her fully justified death sentence had been pronounced no plea for clemency was made, since there was absolutely no case for the defence.’

Mata Hari was to be taken seriously. Many an actress has seen her career enhanced by playing tragic roles in films of espionage or romance. Indeed, from Fritz Lang’s Spione onwards the female spy became a plum role which allowed the actress to deliver a complex performance – these were typically strong, sly, intelligent and alluring characters, adept at concealment, pretence and sexual manipulation, and eventually redemptive conversion.

In 1937 – six years after Greta Garbo starred in George Fitzmaurice’s Mata Hari and three years after Mirna Loy brought the figure of Mademoiselle Doktor to the screen for the very first time in Sam Wood’s Stambul Quest – Dita Parlo appeared in two parallel spy films, Georg William Pabst’s Salonique nid d’espions and Edmond Gréville’s Under Secret Orders,[6] both of which gave a highly romanticised account of an episode in the life of the enigmatic German spy Mademoiselle Doktor (who also went under the aliases Anne Marie Lesser and Elsbeth Schragmueller). Mademoiselle Doktor had already received a number of literary treatments, in which she was depicted as a great beauty but also a woman of the demi-monde, a world she had left behind for a career in the German secret police.[7]

The film by Pabst shown in France initially portrays this mistress of espionage as a ruthless and clinically efficient individual, although this characterisation later gives way to that of a woman with human frailties when she falls in love with a French agent. This notion of the moralistic conversion of the female spy is a recurrent theme across the genre – it also makes an appearance in the 1936 Capitaine Benoît film Les Loups entre eux, starring Renée Saint-Cyr.

The 1930s also witnessed a great deal of agitation and repression regarding the emancipation of women. The female spies of World War I were therefore seen as figures of strength but ultimately subversive – a source of fascination but also a threat to the patriarchal status quo.

In this climate, Sœurs d’armes, which hit cinema screens in 1937, is a remarkable exception for its unequivocally positive depiction of female secret agents – figures of chastity and courage who rise to the exceptional circumstances in which they find themselves and find solidarity in adversity. The film is a ‘realistic’ dramatisation of the glorious story of Louise de Bettignies and her comrade Léonie Vanhoutte, a woman of far more modest background – both of them celebrated for their clandestine intelligence (and not horizontal espionage) activities during World War I.[8] In his film Léon Poirier emphasises the sacrifice made by Louise de Bettignies, who ‘died for France’ (and, therefore, not for England), as well as the notion of patriotic duty during wartime as a calling which unites all citizens, erasing class divisions.

In its celebration of the two chaste secret agents’ unflagging courage and heroism, the film turns both of the characters into a sort of cross between the French Republican heroine Marianne and the Christian saints (a theme which was to blossom in French films made during the Occupation).

Thus we can observe that in the mid-1930s French cinema represented two of the most famous female spies of the Great War, Mademoiselle Doktor and Louise de Bettignies – the former an enemy agent, the latter working for France. Unlike the Americans, the French chose not to make a film with Mata Hari as the central character; this did not happen until 1964, when Jean-Louis Richard cast Jeanne Moreau in the role. Nevertheless, the French felt that the story of the Dutch double agent concerned them directly. She had been a celebrity in Belle Epoque Paris, where she appeared first as an exotic-erotic dancer at the Musée Guimet in 1905, causing a sensation, and then as a scandalous courtesan adored by some of the most influential members of the upper class.[9] It is tempting to echo the thoughts of a new generation of historians who have considered her case, seeing in her an exemplary sacrificial victim for France who came along just when the French army was experiencing difficulties against the Germans.[10] It should not be forgotten that Mata Hari, alias the Red Dancer, was herself also the creator of her own myth – at a time when orientalism was highly fashionable, she played on her supposed Javan origins and exotic status as a priestess of the cult of Shiva. All of this lent her the aura of somebody out of the ordinary, rather than a mere informer who swapped sides as she changed beds – and indeed, this is reflected in the MGM film, in which Mata Hari is given the hieratic features of Greta Garbo.

There are elements in the part Sternberg wrote for Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored which clearly allude to the Mata Hari legend (the film is often cited in studies of the history of cinema as a work about the Red Dancer). Dietrich plays the part of agent X27, a larger-than-life character who demonstrates that for both Sternberg and Hollywood in general Mata Hari was a mythical figure, a fascinating woman who fell victim to men’s cruelty and the harsh laws they devised.[11]

Here, then, is a summary of the main elements of the context in which Raymond Bernard’s film was made, a film which appeared in cinemas the same year as Léon Poirier’s Sœurs d’armes: first, in France people were alarmed by the escalating problems in Europe and the threat of a new general conflict. Second, the female spy was quite a popular figure in film, the best example being Mata Hari in Hollywood movies. Finally, patriotic French figures from the last war were being raised to prominence.

However, while Louise de Bettignies, the ‘Joan of Arc of the North’, was one of espionage’s great figures and a true martyr[12] – her most notable achievement being to have tipped off Joffre about the German offensive on Verdun – Marthe Richer, aka Marthe Richard, is altogether more problematic.

However, Marthe Richard became soon a high-profile figure. Born in Lorraine in 1889 (when the region was under German occupation) she first came to the public’s attention in 1913, when she obtained the pilot’s licence she was to display whenever she went to an airfield looking for thrills and adventure. A Russian pilot, Joseph Davritschevy (also known as Jean Violan and Zozo), became her lover and introduced her to the head of French military counterespionage, Georges Ladoux, for whom she worked from June 1916 until December 1917. Her second mission took her to Madrid,[13] following an inauspicious beginning in Sweden – an attempt to penetrate a German spy network which failed completely but provided Lajos Biró with the inspiration for a screenplay, The Dark Journey, directed by Victor Saville and produced by Alexander Korda in 1937. In the film Vivien Leigh plays an unfortunate French spy who manages to infiltrate a German spy network in Stockholm but is soon discovered, only to be saved in extremis by an English secret agent. At the time the film was made, Marthe Richard was remarried to a wealthy Briton, Thomas Crompton. Marthe Richard-Crompton also became a well-known figure in Britain, where her memoirs and those of Ladoux were translated and read. Before the outbreak of World War II, Editions de France and John Long Publishing produced three books by Marthe Richard in quick succession – Ma vie d’espionne (My Life as a Spy) was published in 1935, followed by Espions de guerre et de paix (Spies in War and Peacetime) in 1938, after the release of the film, and finally Mes dernières missions d’Espagne (My Last Assignments in Spain) in 1939.

II – Fabrication of a new myth through the demystification of the Mata Hari legend: the virtuous and patriotic Marthe Richard

This, then, was the as yet relatively untarnished figure – the slings and arrows of the press and police were to follow later – whom Raymond Bernard took as the heroine of his patriotic spy film, produced by the Hakim brothers.

As the title of the film clearly indicates, the purpose of Marthe Richard au service de la France was to paint the picture of an agent devoted to her homeland. Raymond Bernard’s film set about creating a new cinematic legend – a female spy from Lorraine who was French through and through, unlike the cosmopolitan, itinerant figure of the fake Javan; a secret agent who was not only patriotic but victorious; better still, and especially appealing to national pride, a virtuous heroine who refused to surrender her modesty to the enemy – she does no more than promise the German master spy that she will be hers after the assignment is over – and rose above the easy virtue, loose living and depravity of a high-flying prostitute like Mata Hari.

Of course, the new myth of the positive, chaste heroine could only be constructed once Mata Hari had been well and truly knocked off her perch. Marthe, France’s heroine, needed to confront the infamous agent H21, to grapple with and defeat the woman who had betrayed ‘her beloved Motherland’.

As it turns out, the two are rarely brought together in the film. They cross paths in the German attaché’s apartment, where their confrontation is both brief and merely verbal. In her one exchange with the shabby, faded dancer, Marthe manages the tartly humorous remark: ‘You’re dressed! I didn’t recognise you!’ The two women are genuine rivals, however, in the affections of von Lüdow, Marthe’s main enemy, and it is by using him that she devises a stratagem to do away with Mata Hari once and for all. Without giving herself away, Marthe presents von Lüdow with fabricated evidence of what is in fact going on – the dancer’s double-crossing of the Germans. Thus Raymond Bernard’s version of the story ends up chiming with what was thereafter generally taken to be the truth – that Mata Hari was handed over to the French police by the Germans!

Raymond Bernard clearly constructs the two characters, Marthe and Mata Hari, in diametric opposition to one another. Marthe is a picture of lofty patrician elegance in her spy’s apparel. Edwige Feuillère, who was destined to become the grande dame of French cinema,[14] takes full advantage of this opportunity to display what would become her trademark style. While Feuillère was not yet a celebrated star of the big screen, she had attracted some attention in the role of Lucretia Borgia, the eponymous heroine of Abel Gance’s 1935 film.[15]

On the other hand, the actress playing Mata Hari, Délia Col, was a complete unknown at the time the film was released, and remained so for the rest of her career. Where Feuillère’s Marthe is coolly aloof, Col’s Mata Hari is slatternly, vulgar, totally lacking in class while trying to be elegant. From the moment the actress first appears in the Spanish club, the image of the alluring, erotic dancer of the Musée Guimet is shattered. The actresses were clearly cast in order to exacerbate the contrast between the two female leads – Marthe’s physical and moral qualities are elevated in inverse proportion to those of Mata Hari, who from the beginning is depicted as physically unprepossessing and morally degenerate.

While Mata Hari pesters the indifferent Lüdow for affection, begging him to kiss her and, when he eventually agrees to do so, pleading with him to take his cigarette out of his mouth and do it properly, Marthe feigns coyness, threatening Lüdow with a revolver and refusing him a kiss. Marthe is imperious; her rival abases herself, losing all poise and dignity – spurned and jealous, she soon betrays her ill breeding, squawking like a fishwife and stamping her feet in a frenzied tantrum. Raymond Bernard forces the point home – Mata Hari has never possessed a shred of honour or dignity. She is depicted as an infatuated and venal harlot, and ultimately nothing more than a vulgar murderess.

III – Feuillère and Stroheim: Marthe Richard as a vehicle for two actors at a pivotal moment in their careers

The film Marthe Richard enjoyed some success in 1937 – as historian Colin Crisp explains, although it did not race to the top of the box-office list, it held its place among the ten most popular films in France.[16]

In 1936 Stroheim’s Hollywood career seemed to have reached a dead end, but things turned around when he received an invitation from Maurice Tourneur to join him in France and star in his film Koenigsmark. Stroheim declined, but immediately accepted a rival offer from Raymond Bernard. In November 1936, feeling quite at home with the role he was to play – Baron von Lüdow – he cut his ties with MGM and left for Paris. His biographer, Richard Koszarski, stresses that Stroheim bought a return ticket, clinging to the hope that after Marthe Richard he would return to America and direct another film.[17] However, Marthe Richard proved to be a new departure for Stroheim, who ended up staying in France and starring in nine films in rapid succession up to the year 1939. One film in particular guaranteed him immortality – it was, of course, La Grande illusion. In many respects his interpretation of von Rauffenstein in this film echoes his earlier performance as von Lüdow, Stroheim slipping comfortably into the character of the mannered, fetishistic German aristocrat, a man apparently paralysed by pride but, deep down, ravaged by contradictions. These two rich and nuanced characters won Stroheim new renown as an actor, allowing him to leave behind the grossly caricatural roles – the sadistic Uhlan subaltern, the spoilt, decadent prince – which during the days of silent film had earned him a reputation for brute flamboyance. Three films from 1918 see him in the grotesque role of the Hun who wreaks total destruction around him – The Unbeliever by Alan Crosland, Hearts of the World by D. W. Griffith and The Heart of Humanity by Allen Halubar. There can be little doubt that, at the age of 52, Stroheim had finally found in Marthe Richard a film which offered him a role worthy of his talents. He went on to play the role of a fallen agent – mirroring, perhaps, his own trajectory as a fallen director – in several spy films, including Gréville’s Mademoiselle Docteur (1937) and Fyodor Otsep’s Gibraltar (1938). Billy Wilder’s 1943 film portraying operations in North Africa, Five Graves to Cairo, gave Stroheim another role worthy of him, that of General Rommel.

Edwige Feuillère left the Comédie Française in 1933; her acting career then saw her typecast by turns as a maid or a coquette, both on stage and on film, until 1935 when, as we have seen, Abel Gance cast her (no doubt because of her physique) in the leading role of Lucrèce Borgia. The nude scene she performed in the film was deemed scandalous but certainly pulled the crowds in. For her as for Stroheim, Marthe Richard was something of a turning point, even an apotheosis, since it elevated her to a role of real depth, a role which she made her own and which defined her career thereafter. She was now playing a woman of strength and spirit, a real headline act. The role of Marthe Richard, then, might be seen as a gift for Feuillère, one which gave her the opportunity to stretch out her talents as a mature screen actress, and indeed, the opportunity to create a myth. Marthe Richard’s Racinian rhetoric of hate and duty dramatises and blends her intoxication by vengeance for the murder of her family and her voluntary submission to the requirements of governmental Intelligence. Feuillère was called upon to perform a complex, multi-faceted character who in the course of the story develops from childhood innocence to adult disillusion, and the recognition the film brought earned her a string of leading parts in other films: before the German invasion she starred for Marc Allégret in La Dame de Malaga, for Max Ophuls in Sans Lendemain and De Mayerling à Sarajevo, and then for Raymond Bernard again in J’étais une Aventurière. During the Occupation Feuillère’s crowning glory came with Giraudoux’s adaptation of Honoré de Balzac’s La Duchesse de Langeais, directed by Jacques de Baroncelli, but she also enjoyed popular recognition in a number of American-style screwball comedies, such as L’Honorable Catherine by Marcel L’Herbier.

Geneviève Sellier proposes an interesting theory on the strong roles played by Edwige Feuillère in films, paying special attention to her performance as Marthe Richard. Unsurprisingly, Sellier concentrates on the battle between the characters played by Feuillère and Stroheim. As she rightly observes, the twists and turns of the espionage plot eventually give way to a number of highly polished scenes of dialogue between Feuillère and Stroheim. Raymond Bernard’s directing makes more use of expressionist darkness than the conventional light of romance, and his camerawork on the two actors alternates dynamically between medium shots and close-ups, enhancing the dramatic power of the actors’ performances. Sellier concludes: ‘Feuillère is beautiful, haughty, distant and, above all, ruthlessly efficient. She must therefore be brought to heel in exemplary fashion. The sequence which epitomises this need for constant humiliation comes at the climax of Marthe Richard, when Edwige Feuillère has just revealed to her lover, the German intelligence officer (Eric von Stroheim) that she has successfully completed her mission: the sinking of the U-boat fleet it was his job to protect. Without a flicker of emotion, Stroheim lifts his fingers from the keys of his piano, takes a syringe and administers himself a lethal injection. Feuillère, meanwhile, is the victor in the masculine sphere of war, but has been defeated in the feminine sphere of sentiment which for her, it is presumed, counts for more. Wrong-footed by this gesture of supreme masculinity, she ends “her” story as a petrified onlooker, powerless before the tragic death of her lover and adversary.’[18]

A further question Sellier poses is whether Raymond Bernard’s narrative makes an amorous relationship possible between these two characters, and if so, whether Marthe Richard might ultimately have fallen victim of the love trap she set up for her arch-enemy – thus conforming entirely to the already established conventions of the spy genre.

We would venture to suggest that the film aims to do much more than dramatise a ‘taming of the shrew’ and a classic honey trap. The disturbed, and indeed disturbing, world depicted by Bernard is one of all-out espionage in which the death toll rises and rises – Marthe Richard is the sole survivor of the events which take place behind closed doors in San Sebastián – but also, indeed especially, a theatrical world in which everything has to be illusion, sham and deception.

In his enthusiastic commentary on the film included in the 2006 DVD release, Noël Simsolo identifies this all-pervading sense of theatre and untruth, where the loser is the person who is unable to maintain the ability to deceive. The film, then, is not conceived as a sentimental drama and so manages to avoid the romantic clichés which typify previous films about female spies – this, in our opinion, is what makes Feuillère’s and Stroheim’s parts valuable and original work, worthy of our attention.[19]

Stroheim/von Lüdow, the formidable master spy so feared by the French secret service, commits the fatal error of dropping his guard. A victim of his both his arrogance and his own illusions, he makes the supreme error of acting with complete sincerity, believing in ‘the great adventure’ he thinks he is having with the young woman he has educated, moulded and elevated to his aristocratic level. This is the dramatic folly of an ageing manipulator. This oxymoronic figure, the sincere and ignorant spy, fails to recognise that the woman he has before him is ‘Cosette turned Jeanne Hachette’ – all he can see at first glance is the sensual élégante, the incarnation of Parisian chic, on a plate for his enjoyment. His fate is sealed the moment he falls prey to feelings which in this film genre are usually the preserve of women. Nonetheless, Stroheim’s character develops considerably in the world of lies he inhabits, where he is still able to manipulate those around him, except for Marthe. Lüdow’s sombre character is elevated by Raymond Bernard’s camerawork, in particular the chiaroscuro effects he deploys – expressionist photography, contrasting light and oblique angles. We always meet him in baroque settings – his apartment is lavishly ornamented with reflective objects and chandeliers – which suggest both Stroheim/Lüdow’s addictive love of finery and his bedazzlement by the tricks of the woman he has fallen in love with.

This role reversal in Raymond Bernard’s drama confronts and defies the genre formula. It is underlined interestingly in the final scene of the film, the victory parade in Paris, in which Feuillère appears dressed in a manner redolent of the sombre, solitary hero of the film noir – she has ditched her smart, bright clothes and her various disguises for a man’s trenchcoat and trilby. The scene is set in 1919, and Feuillère’s style of dress looks particularly out of place and time amid the weeping women, all dressed in their widow’s weeds, who crowd the front rows on the Champs-Elysées.

The film’s strong emphasis on mixed identities may be also explained by the fact that Raymond Bernard had witnessed the many consequences of trench warfare which, directly or indirectly, had ravaged every level of French society. His dramatisation of these torments seems prescient of the new terrors which were to follow: with the collapse of France in May 1940 nobody would know for certain who was a collaborator and who was a genuine member of the Resistance. Bernard seems to foretell this atmosphere of distrust in his staging of a time when deception, lies and confusion are the only chance to escape and survive. He was to return to this sense of confusion and refashion it in the film he made just after the Liberation, Un Ami viendra ce soir, one of the very first French films about the Resistance.

Conclusion

Marthe Richard au Service de la France is certainly a film of significant riches, despite its disjointed style, which some may have found off-putting, and the poor special effects of the time, which might disappoint today’s audiences. Although it did not receive the recognition it deserved in the decades following its release, especially in the days of the Young Turks of the Nouvelle Vague, it did not go entirely forgotten. On 24 February 1971 it received a prime-time airing on French national television in the first part of Armand Jamot’s famous series, Les Dossiers de l’Ecran. A whole new generation of viewers was introduced to the ‘remarkable’ career of Marthe Richard. In truth, what they were really being introduced to was the trial of an old woman best known since 1946 as the instigator, or rather the person who lent her name to the law introduced to close down French brothels. The systematic destruction of Raymond Bernard’s beautiful legend of the courageous woman spy had in fact begun in 1947 with the poisoned pen of her former lover, the Russian pilot Jean Violan. Writing in the issue of the popular weekly France Dimanche which appeared on 3 August 1947, under the evocative title ‘The truth about Marthe Richard’ Violan disputed the success, integrity and chastity of his former lover. In 1952 an issue of Le Crapouillot continued the campaign against Marthe by publishing her portrait alongside that of Mata Hari on its front cover, followed by the text: ‘Thanks to their prodigious talent for scheming and lying these women have added further strands to the tangled web of espionage.’ From 1953 onwards, the police would not let up their pursuit of Marthe Richard. In 1954 a number of police files were published in the magazine Noir et Blanc under the title ‘Marthe Richard, 40 years as an impostor’.

In the 1971 programme mentioned above, after the screening of Raymond Bernard’s film millions of French viewers were treated to the sight of Charles Chenevrier, the former assistant director of criminal affairs at the Sûreté Nationale, giving a string of sensational revelations against the legendary spy: her days as a prostitute in Nancy at the age of 16, the total ineffectiveness of anything she did in World War I, her abject collaboration with the occupying forces in World War II, petty theft and harbouring of stolen goods, charges brought against her and her subsequent imprisonment . . . In the centre of Armand Jamot’s TV studio Marthe Richard, now an old woman of 82, listened to all this without so much as a flicker. The brickbats never ceased – the latest came after her death, in an article written by Mary Blume in the International Herald Tribune on 3 August 2006, entitled ‘A postwar heroine who fooled France – the secret past of Marthe Richard’ and published to coincide with the DVD release of Bernard’s film: ‘Blessed with the boldness of a true pathological liar, she had covered her tracks for decades as she rose to respectability . . . She was a charmless Mythomaniac.’

Hence it is tempting to conclude that the film, hampered by a central figure who had become so ambiguous and widely vilified, indeed harmful to the legend of the fictional heroine, was never going to be readily accepted into the canon of classic cinema. In short, the myth didn’t stick. However, was it ever going to catch on in a society which, unlike those of England and America, naturally shies away from exalting its spies – in civil life as on stage and screen? Furthermore, while the falsely virtuous Marthe Richard of real life soon destroyed her public persona, the Marthe Richard of the film seemed to offer at best an ambiguous message: she was spurred to do what she did less out of love of her country than thirst for personal revenge. Nevertheless, both the character and the film have acquired a kind of symbolic status, becoming an often ironic reference point. It is in this spirit that André Bazin, in his essay Le Cinéma de la cruauté, chose to criticise Alfred Hitchcock’s film Notorious (which he disliked) by accusing the screenwriter Ben Hetch of having lazily reproduced Raymond Bernard’s screenplay, with Marthe Richard now serving not France but the Atom Bomb! Marthe’s symbolic status, it would seem, lives on . . .

Clara Laurent – Paris X University

Pierre Lethier – King’s College London

[1] 15 ans d’années trente: le cinéma des Français 1929–1944 (Stock Cinéma, 1983), p. 229.

[2] La Vie Est à Nous – French Cinema of the Popular Front 1935–1938 (London: BFI, 1986).

[3] This is echoed in the figure of Sergeant York, the hero of the Great War whose function in Howard Hawks’s 1941 film is to issue a rallying cry for the United States to intervene in World War II.

[4] In 1937 the press was full of stories of secret agents; the affair of the embezzler Stavisky, who was bumped off because of his relations with the secret service, was talked about extensively, though to no effect.

[5] Female spies had already become very popular in silent movies, through films such as Fritz Lang’s Spione in 1927 and Fred Niblo’s The Mysterious Lady in 1928, in which Greta Garbo played the femme fatale of the film’s title.

[6] Pabst’s film also starred Pierre Fresnay and Pierre Blanchar, while Gréville’s parallel version, which was filmed at the same time and based on the same script, starred John Loder and Erich von Stroheim.

[7] Mademoiselle Doktor’s memoirs were serialised in the Eclaireur de Nice in the late 1930s.

[8] Major Thomas Coulson, in his book The Queen of Spies, Louise de Bettignies (London: Constable & Co., 1935), appropriates the story of the polyglot heroine, recounting how she entered the British Secret Service (and not the French Intelligence Bureau), where everyone knew her as Alice Dubois. She created a network of informants comprised of Belgian dressmakers – ‘Coquettes they may have been, but prostitutes never!’ (p. 72).

[9] Mata Hari played herself in a dance film made in Paris in 1913 by the Italian Cappelani. This ‘art film’ was later exported to the United States.

[10] The year 1917 had seen the slaughter of the failed Nivelle offensive in April, widespread mutiny in May, strikes in June and a string of treason scandals throughout the summer.

[11] For some authors, however, Mata Hari is above all a victim of other women’s cruelty: in Espionage (1930), Hans Berndorff insists that she was reported to the authorities by Hanna Witting, the jealous wife of the Count of Chilly, who according to Berndorff pursued a brief career in film under the name Claude France. Hanna Witting was apparently racked with guilt and eventually committed suicide in Paris in 1928. In his encyclopaedia The Espionage Filmography, 1898 through 1999, Paul Mavis cites Mirna Loy: ‘I made my last stand in exotica as Fraülein Doktor, the spy who captured Mata Hari.’ The historian Ernest Volkman, in Spies: the Secret Agents Who Changed the Course of History (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1994), states that it was indeed Fraülein Doktor who turned the dancer in to the French police.

[12] See Antoine Redier, La Guerre des femmes (Paris: Editions La Vraie France, 1924).

[13] According to Major Rivière in Madrid, Centre de Guerre Secrète (Paris: Payot, 1936), Marthe Richard was one of several female spies sent to Madrid at this time.

[14] Edwige Feuillère was voted best French actress in 1946.

[15] This was Feuillère’s fifteenth screen appearance. Her film career began in 1931, in which she featured alongside Fernandel in André Chotin’s minor comedy La Fine Combine, followed in 1932 by a film version of Tristan Bernard’s play Le Cordon Bleu.

[16] Colin Crisp, Genre, Myth, and Convention in the French Cinema 1929–1939 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002), p. 300.

[17] Richard Koszarski, The Man You Loved to Hate (Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 280.

[18] Geneviève Sellier and Noël Burch, La Drôle de guerre des sexes du cinéma français, 1930–1956 (Paris: Nathan, 1996), p. 54.

[19] Following the example of the great British pioneers of the spy narrative who established the fundamental principles of the genre, John Le Carré often said that the art of spying is essentially a theatrical performance.